The indigenous Pygmy peoples have ties to their land and natural resources. They are primitive peoples who rely on hunting, fishing, gathering and foraging for subsistence. Their lifestyle is unlike that of other social groups like the Bantu, Nilotes, etc.

These peoples are hospitable and enjoy living alongside others. They are peaceful and social. They have lost their languages. However, most speak the languages of their dominant neighbors. Their socioeconomic and cultural living conditions differ from those of other communities.

The Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI) commissioned a series of national reports on the situation of indigenous peoples in relation to human rights and criminalization. The reports are from IPRI’s 6 focus countries, namely (1) Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in Africa, (2) India and (3) the Philippines in Asia, and (4) Brazil, (5) Colombia and (6) Mexico in Latin America. These 6 countries were identified in consideration of the worsening situation of human rights violations and, systemic criminalization and discrimination against the rights of indigenous peoples.

These national reports aim to raise awareness and attention to the serious violations of the rights of indigenous peoples in these countries. IPRI is the lead organization of the global campaign called Global Initiative to Prevent Criminalization of and Impunity Against Indigenous Peoples. These reports are important and useful for IPRI’s evidence-based advocacy, which IPRI carries out together with its partner-organizations, affiliate organizations and allies at the national, regional and global levels.

Each country report contains a general overview on indigenous peoples based on available demographic data, description of existing laws recognizing indigenous peoples’ rights, and discriminatory laws against indigenous peoples, including in relation to their criminalization. It also provides a general description of the human rights situation of indigenous peoples in the country, including specific cases of human rights violations that took place in 2019.

This report is a preliminary and introductory report. It does not intend to provide in-depth information or historical accounts on indigenous peoples. IPRI endeavors to undertake more researches and publish more thematic reports relating to indigenous peoples’ rights as we advance the Global Initiative to Prevent Criminalization of and Impunity Against Indigenous Peoples.

IPRI wishes to acknowledge the lead writer of the report on the national situation of indigenous peoples in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Diel Mochire Mwenge, a Batwa leader and the provincial Director of Programme Integre Pour Le Developpment Du Peuple Pygmee Au Kivu. IPRI also wish to express its appreciation to his organization as its country partner in DRC and for the full support they have provided in the preparation of this report.

The indigenous Pygmy peoples have ties to their land and natural resources. They are primitive peoples who rely on hunting, fishing, gathering and foraging for subsistence. Their lifestyle is unlike that of other social groups like the Bantu, Nilotes, etc. These peoples are hospitable and enjoy living alongside others. They are peaceful and social. They have lost their languages. However, most speak the languages of their dominant neighbors. Their socioeconomic and cultural living conditions differ from those of other communities.

The forests once occupied by indigenous Pygmy peoples – their ideal natural living environment – have been transformed into national parks, natural and/or community reserves, or hunting grounds, forcing them to leave the forests and settle on the fringes.

The most frequently reported violations committed against the indigenous Pygmy peoples in the Democratic Republic of Congo include violations of rights to land ownership. The despoliation, dispossession, expropriation and then expulsion that they have experienced at the hands of their neighbors the Bantu – for the most part farmers, loggers, mine operators, and guardians of protected areas – and with the help of local and customary authorities, explain this land instability. The country’s laws guarantee equality, in theory, for all citizens. But on the ground, Pygmy natives face a significant problem of access to land and natural resources.

The traditional land and territories managed, occupied or used by indigenous Pygmy peoples are exploited without their free, prior and informed consent. Furthermore, they do not share in the benefits of the exploitation of their natural resources. They live in a state of underdevelopment for numerous and varied reasons. As a result of these inequalities, they have trouble accessing basic social services such as education, health care, drinking water, and adequate housing. The architecture and organization of the Congolese education system clashes with the socioeconomic situation of the Pygmies of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

What is getting worse is the expropriation and exploitation of the land and resources of indigenous people in the name of development in the form of mega-infrastructure, extractive industries, agri food, real estate development, and even commercial tourism, in addition to climate solutions such as large hydroelectric dams, renewable energy projects, and bio-fuel plantations. Many of these projects do not respect indigenous peoples’ rights to their land and resources, and are undertaken in bad faith, without following the appropriate course of action to obtain indigenous peoples’ free, prior and informed consent.

These constraints have thus given rise to conflict, and when indigenous peoples claim and defend their collective rights legitimately, they are subject to harassment, defamation, arrest, incarceration, and even extrajudicial executions. This is in direct contravention of their fundamental rights and freedoms, such as freedom of expression and movement, and the right not to be arrested, to organize appropriately and assemble peacefully, among others.

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE DRC:

GENERAL DEMOGRAPHIC AND SOCIOECONOMIC SITUATION

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is made up of four large ethnic groups: the Bantu, Nilotes, Sudanese, and Pygmies. The first three are the result of different waves of migration in African countries. It is widely accepted that the Pygmies were the first inhabitants of Central Africa, and joined later by farmers and stockbreeders.¹

Based on the criteria established by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, notably the history of occupation of the territory, self-identification, marginalization, discrimination, exclusion leading to sub-dominance, and the preservation of cultures that are distinct from those of dominant groups, the Pygmies’ status as indigenous peoples has been recognized in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.²

Based on the criteria established by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights, notably the history of occupation of the territory, self-identification, marginalization, discrimination, exclusion leading to sub-dominance, and the preservation of cultures that are distinct from those of dominant groups, the Pygmies’ status as indigenous peoples has been recognized in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.²

The exact number of indigenous Pygmy people in the DRC is unknown. No official census has been organized by the Congolese government. However, a study by the World Bank³ in 2009 estimated the population to be around 750,000, of whom 53% were women and 65% youth. Today, they are believed to number a million, which is over 1% of the population of the DRC.

The different “Pygmy” groups are generally known locally as Batwa, Batswa, Batoa, Balumbe, Bilangi, Bafonto Samalia, and Bone Bayeki in the province of Équateur; Batsa, Batwa, and Bamone Bakengele, in the province of Bandundu; Bambuti, Baka, Efe, and Bambeleketi, in the Orientale province; Bashimbi (Bashimbe), Bamboté, Bakalanga in the province of Katanga; Batwa (Batswa) in the two Kisai provinces; Batwa (Batswa), Bambuti, Bayanda, Babuluku, Banwa, Bambuti, and Bambote in North Kivu, South Kivu, and Maniema. Other groups are distributed throughout the forest region of the DRC, notably the Aka, along the north-west border with the Republic of Congo, and the Bambega on the Oubangui in Équateur.

The Pygmies’ socioeconomic life remains fragile. Their socioeconomic rights are not respected. Most Pygmies live in forests, in inaccessible areas. Access to social infrastructure is very limited. Poor levels of education of indigenous children, limited access to healthcare,drinking water, information, and markets, and an average distance between infrastructures that ranges from 12 to 25 km⁴ all have an impact on these peoples, who experience high rates of morbidity and mortality.

Pygmies live in extreme poverty; daily household income is under US$ 1. As a result, they are unable to cover and address their basic needs such as food and adequate housing, and 98% live in rudimentary huts (huttes).

High education fees are observed each year in the DRC, making it difficult for Pygmy children to access education as a result of parents’ poor purchasing power and extreme poverty. Access to education among Pygmy children of school age varies across regions. The highest rates, for example, are found in South Kivu and North Kivu, where between 4% and 11% have access to primary education.⁵

High education fees are observed each year in the DRC, making it difficult for Pygmy children to access education as a result of parents’ poor purchasing power and extreme poverty. Access to education among Pygmy children of school age varies across regions. The highest rates, for example, are found in South Kivu and North Kivu, where between 4% and 11% have access to primary education.⁵

The Congolese government offers a healthcare program and special support programs for health institutions. However, it is difficult for health institutions founded by indigenous Pygmy peoples in their communities to benefit from this support by the Congolese government. Most Pygmy women give birth at home, and few attend prenatal and postnatal consultations. In North Kivu, out of 11,651 women in 164 villages/places, 4,217 have access to these services in 67 villages/places, or 36%. Of 19,719 Pygmy children, only 4,761, or 24%, have access to a vaccination program.

This lack of access to health care is the result of insufficient information. In 2016, 53% of the Pygmy population was unaware of the health education sessions organized in health centers. In addition, for lack of funds, Pygmy women give birth at home, with various consequences: between 2016 and 2018, in North Kivu, it is estimated that 5 women died in labor, and 7 women who gave birth by cesarean section were held in hospitals.

For the Pygmies, land is an economic and cultural asset, and they have strong ties to their land and the resources it provides. Indeed, their lives depend on it. They live in traditional areas acquired customarily, and which are predominantly managed collectively, a form of management not yet recognized by land law. For this reason, as the land has no legal personality, it is registered in the name of NGOs, churches, and individuals, which represents a risk of expropriation and despoliation of the land.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF LAWS AND POLICIES RELATING TO INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

- At an international level

The United Nations and its system offer mechanisms to address the issue of indigenous peoples’ human rights by putting in place legal mechanisms and texts to promote and defend the rights of indigenous peoples at an international level. The system calls on states to comply with human rights protection instruments they have ratified and provides for redress mechanisms when states do not meet their international legal obligations.

- International mechanisms for the protection of the rights of indigenous Pygmies

Mechanisms are international channels for the protection and defense of the human rights of indigenous peoples, including Pygmies, some of which are specifically referred to in indigenous rights issues. This system calls on states to comply with human rights protection instruments they have ratified and provides for redress mechanisms when states do not meet their international legal obligations.

They include:

- The UN’s Decades of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (1994-2005 et 2005- 2015);

- The International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples, commemorated on August 9th each year;

- The UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People;

- The United Nations Forums on Indigenous Peoples;

- The Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII)

- The Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Meetings by monitoring bodies for UN treaties and conventions

Human Rights Council (through the Universal Periodic Review of country reports in the March and September sessions: a means to carry out checks, at an international level, on states’ commitment to the protection of indigenous peoples’ rights).

Meetings by monitoring bodies for UN treaties and conventions, such as the CERD⁶, CEDAW, the Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC and CBD, experts’ meetings on intellectual property (division on indigenous peoples’ rights to traditional recognition), and the Human Rights Council (through the Universal Periodic Review, which places particular emphasis on the human rights situation of indigenous peoples). - Legal instruments for the protection and defense of the rights of indigenous peoples

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

Articles 1 and 27 provide for a people’s right to self-determination, cultural integrity, land and resources, means of subsistence, and participation (ratified by the DRC); - The International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD):

Protects the rights of IPs to possess, exploit and control their wealth, and requires fair and equitable compensation in the event of privatization. This instrument addresses the question of differential treatment for a particular group to remedy the historical discrimination endured by certain ethnic groups (April 21st, 1976, accession and ratification by the DRC); - International Labor Organization Convention 169 on indigenous and tribal peoples:

Contains a number of provisions on indigenous peoples’ territorial rights. Article 13(1) requires that states recognize and respect the special importance, for cultures, economies, and spiritual values, of indigenous peoples’ relationship with their lands and territories. Article 14 provides that, for indigenous peoples, “rights of ownership and possession […] over the lands which they traditionally occupy shall be recognized.” It also states that “governments shall take steps as necessary to identify lands which the peoples concerned traditionally occupy, and to guarantee effective protection of their rights of ownership and possession.” This convention is important in addressing the issue of land and forest tenure in indigenous communities; - The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD):

Establishes standards for the sustainable management of biodiversity and natural resources for the benefit of future generations. It records governments’ commitment to take into account the traditional knowledge and practices of indigenous peoples in theconservation of natural resources, and above all, the equitable sharing of benefits from genetic resources (Article 8(j) and 10(c)); - The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP):

The Declaration places particular focus on the rights of IPs to ancestral lands and resources. It calls on governments to provide legal recognition and protection to these lands, territories, and resources. IPs have a right to redress and, unless they decide otherwise, such compensation shall take the form of equivalent lands, territories, and resources (Articles 25, 26, 27, and 28); and - The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR).

- The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR):

- International mechanisms for the protection of the rights of indigenous Pygmies

-

At a national level

No national law exists recognizing the specific rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, since 2011, advocacy efforts have been underway to pass a law to promote and protect the specific rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples, a draft bill for which was presented to the National Assembly in 2016.

However, two provincial laws (edicts) were passed in 2018 in the provinces of Sankuru and Mai-Ndombe to promote, protect and defend the rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples, namely:- Order-Edict n_002/018 dated 29-JUN-2018, on the protection and promotion of the Batwa indigenous peoples in the province of Sankuru; and

- Edict N° 011/2018 dated 05-JUN-2018, on the promotion and protection of the rights of Batwa indigenous peoples in the province of Mai-Ndombe.

These provincial laws, known as edicts (édits), strengthen the government’s commitment to build, throughout the two provinces, a fairer society where the behaviors, aspirations, and different needs of the indigenous Pygmy peoples are taken into account. These edicts seek to protect, promote, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by indigenous Pygmy peoples, while guaranteeing respect for their inherent dignity.

LAWS AND POLICIES USED TO CRIMINALIZE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

The Democratic Republic of the Congo has good legislation, but implementation still poses serious problems. In other cases, laws are misinterpreted or not implemented.

This legislation includes:

- LAW 87-010 on the Family Code (Official Gazette of Zaire, special issue, August 1st, 1987), dated August 1st, 1987;

- ORDER 11/CAB/VM/AFF.SO.F/98 on the creation and organization of the National Council for Children, dated May 13th, 1998. (Ministry of Social Affairs and Family);

- ORDER SC/0133/BGV/CDFAM on the creation and organization of a provincial council for children in the city of Kinshasa, dated August 13th, 1998;

- ORDER SC/0135/BGV/CDFAM on the creation and organization of a permanent secretariat for the provincial council for children in the city of Kinshasa, dated August 13th, 1998;

- DECREE – Administration and liquidation of estate left in the Belgian Congo when there are no grounds for applying the provisions of the Decree dated December 28th, 1888, dated April 3rd, 1954;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER – Estate of Belgians and foreigners deceased in the Congo, dated June 1st, 1960;

- LAW 73-021 on the general property regime, land tenure, real estate regime and securities regime, dated July 20th, 1973;

- ORDINANCE 74-148 on implementing measures for Law 73-021 dated July 20th, 1973 on the general property regime, land tenure, real estate regime and securities regime, dated July 2nd, 1974;

- ORDINANCE 84-026 on the repeal of ordinance 74-152 dated July 2nd, 1974 regarding abandoned or unexploited property and other assets acquired by the state under the law dated February 2nd, 1984;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 1440/0129/93 on the creation of the National Registry for Real Estate Titles responsible for emphyteuses, dated September 20th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 009/93 on the creation of four land registry districts in the city of Kinshasa, dated May 12th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 019/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Bandundu, dated May 20th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 022/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Équateur, May 22nd, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 022/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Haut-Zaïre, May 26th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 023/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Kasaï-Occidental, dated May 26th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 024/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Bas-Zaïre;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 026/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Shaba, dated May 28th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 030/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of North Kivu, June 3rd, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 031/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of South Kivu, dated June 3rd, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 032/93 on the creation of land registry districts in the region of Maniema, dated June 4th, 1993;

- MINISTERIAL ORDER 034/93 on the creation of the two land registry districts in the region of Kasai-Oriental, dated June 10th, 1993;

- ORDINANCE 77-040 establishing the conditions for the granting of free concessions to Zairians having provided outstanding service to the Nation, dated February 22nd, 1977;

- ORDER 90/0012 establishing the methods of conversion of perpetual or ordinary concession titles, dated March 31st, 1990;

- DECREE repealing and replacing the Decree dated March 31st, 1926, on land registration rights, dated February 14th, 1956;

- ORDINANCE 74-150 establishing the models of registration books and certificates, dated July 2nd, 1974;

- ORDINANCE-LAW – Transfer and registration of ownership rights and rights to enjoyment of real property registered in the Democratic Republic of Congo, dated November 30th, 1970;

- ORDINANCE 76-199 on the procedure for registering and deregistering rights to real property registered, dated July 16th, 1976;

- ORDER BY THE ADMINISTRATOR-GENERAL OF THE CONGO – Registration and measurement of private property, dated November 8th, 1886;

- SOVEREIGN KING’S DECREE – Demarcation of private property. – Land occupation. – Felling on state-owned land, dated April 30th, 1887;

- DECREE – Measurement and demarcation of land, dated June 20th, 1960;and

- ORDINANCE 98 – Measurement and demarcation of land, dated May 13th, 1963.

DATA ON AND DESCRIPTION OF THE CRIMINALIZATION AND IMPUNITY OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

Defenders of human and land rights face serious risks as a result of their work protecting communities, individuals, and the environment. The nature of their work means they are often the target of state and non-state actors looking to discourage, discredit, and disrupt their activities.

⁸Numerous mining, logging, conservation, and livestock farm projects are underway in the DRC, carried out by multinational companies and private sector stakeholders. The oil exploitation project, both within and outside protected areas, has been undertaken by companies such as the Anglo-French company Perenco, the company Total in the province of Ituri, the South African company Dig Oil in the Salonga Park, and SOCO⁷ in the National Park. The spaces occupied by these companies have been reallocated without the free, prior and informed consent of the communities holding customary land rights.

According to a report by Front Line Defenders, 281 human rights defenders were killed in 25 countries in 2016, a notable increase with respect to 185 in 2015, and 130 in 2014. Most of these cases are associated with land and indigenous and environmental rights, and most killings occurred in Latin America and Asia, but indigenous human rights defenders face growing levels of retaliation worldwide.

According to a 2018 Global Witness report: “Of the 19 land and environmental defenders reported killed across Africa, 17 lost their lives while defending protected areas against poachers and illegal miners – 12 in the Democratic Republic of Congo alone.”⁸

RECOMMENDATIONS

Over the last two years, land and environmental rights defenders have been killed by individuals with no sense of civility. More than 7 Pygmies were killed between 2018 and 2019. This is in addition to 36 Pygmies, including 5 youth, who were arrested, detained and tortured by security services, and the 14 Pygmies who were threatened by mine operators and farmers⁹. In the territory of Walikale, 6 artisanal miners were arrested and imprisoned in Goma’s central prison, Munzenze.

Over the last two years, land and environmental rights defenders have been killed by individuals with no sense of civility. More than 7 Pygmies were killed between 2018 and 2019. This is in addition to 36 Pygmies, including 5 youth, who were arrested, detained and tortured by security services, and the 14 Pygmies who were threatened by mine operators and farmers⁹. In the territory of Walikale, 6 artisanal miners were arrested and imprisoned in Goma’s central prison, Munzenze.

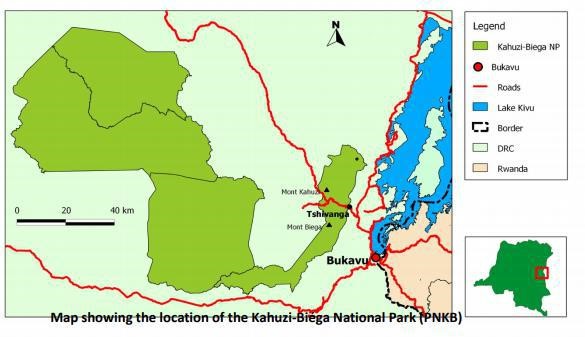

Between 2018 and 2019, 3 rangers were killed, with the most prominent of these killings occurring on Thursday, March 7th, 2019. It should be noted that in this park, a total of 176 guards have lost their lives in the course of their duties¹⁰. Eighteen (18) officials at the Kahuzi-Biéga National Park (PNKB) were kidnapped by Raia Mutomboki rebels, led by Mr. Kikwama¹¹.

In 2014, training sessions were organized for Pygmy land rights defenders in 6 territories in the province of North Kivu. This training course reached 66 defenders who received capacity building on their safety and protection as defenders, with a view to reducing the dangers and threats they faced. Indeed, 22 of these defenders had already experienced threats and dangers in the course of their duties, including arbitrary arrest, torture, and harassment.

DENIAL OF JUSTICE FOR INDIGENOUS PYGMY PEOPLES IN THE DRC

Access to justice for indigenous Pygmy peoples in the DRC remains a challenge. Dysfunctions in the legal system and the Pygmies’ lack of information on legal and judicial procedures are a scourge that must be stopped. Most judges, judicial police officers, judicial police inspectors,and judicial police agents are not familiar with and are untrained in international and regional instruments to protect indigenous peoples’ rights. This is chiefly due to the incompetence of senior officials in the legal and judicial system with respect to the specific rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples given their awareness of the vulnerability and indulgence of indigenous peoples, which has changed their perceptions and frame of mind regarding indigenous Pygmy peoples in the DRC.

Corruption is a problem faced by indigenous Pygmy peoples, and an obstacle to the proper functioning of justice. The vulnerability of indigenous Pygmy peoples means they are unable to address this. They are discredited and discriminated against by those responsible for justice throughout the province of North Kivu. Exchanges between indigenous Pygmy peoples, organizations defending indigenous Pygmy peoples’ rights, and senior officials from the judicial system are called for.

Lawyers and the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights should also take part. If a Pygmy is placed on trial, judges, judicial police officers, judicial police inspectors, and judicial police agents, who are currently not trained to do so, will be able to analyze and make reference to international and regional legal instruments to protect and promote the rights of indigenous peoples, whether or not they have been ratified by the DRC.

The right to justice – an integral part of several articles in the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights – and other internationally agreed legal instruments serve as a reference.

Table 1: Analysis of challenges and constraints

| N° | Challenges and Constraints | Opportunities |

| 1 |

Insufficient information on legal and judicial procedures and the functioning of the judiciary among indigenous Pygmy peoples in the DRC12¹²; |

Discussions and exchanges between IPs and trained Pygmy paralegals International and Regional legal texts that promote, protect, and defend the rights of Indigenous Pygmy peoples, and to which DRC is party. |

| 2 | Poor knowledge among legal, judicial, and prison authorities in North Kivu and South Kivu of international and regional legal texts that promote, protect, and defend the rights of indigenous people. | |

| 3 | Poor access to justice for indigenous Pygmy peoples in North and South Kivu. | Courts (justice of the peace courts) and public prosecutors that improve access to justice for IPs locally. Clear commitment by court officials at all levels following grassroots workshops. |

| 4 | International and regional texts that protect indigenous peoples are not applied in domestic law | Commitment by the DRC in the Universal Periodic Review process, by accepting recommendations on Pygmy issues acknowledged by the DRC. |

| 5 | Inability of indigenous Pygmy peoples to pay legal costs as a result of their vulnerability and poverty. | Possibility of issuing proof of indigence, following a policy of waiving legal costs by way of an order by the chief justice acknowledging an individual’s vulnerability. |

| 6 | Poor recognition of collective and community land tenure in land law. | Land reform underway in the DRC, a decree and order on the forest concessions of local communities in the DRC. |

GENERAL TREND AND REASSESSMENT OF THE PROBLEM OF RESPECT, RECOGNITION, AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PYGMY PEOPLES IN THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Article 51 of the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, adopted in 2006 and revised in 2011, providesthat “the State has the duty to ensure and promote the peaceful and harmonious coexistence of all ethnic groups in the country. It also ensures the protection and promotion of vulnerable groups and of all minorities. It ensures their development.¹³” The country’s constitution makes no reference to Pygmies specifically, which forms the basis for the absence of specific protection guarantees for the rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples in the DRC.

It should be noted that there are specific laws to protect women, children, the disabled, and albinos, as vulnerable groups. Only the Pygmies do not yet have a specific law to protect them, which constitutes a special protection vacuum, in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on September 13th, 2007, by the General Assembly.

However, thanks to state awareness of the specific context of the indigenous Pygmy peoples, some progress has been made over the last 4 years in the DRC. At the national level, a bill for an organic law on the fundamental principles of indigenous Pygmy peoples’ rights was presented to parliament in July 2014. Since then, it has been recorded on the agenda for discussion and adoption by the National Assembly and the Senate, before being enacted by the President of the Republic. It is, thus, a backlog from past legislation.

The lack of information on the development of indigenous Pygmy peoples’ rights has formed the basis for the increase and development of prejudices against indigenous people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Some authorities and individuals believe that passing a specific law on indigenous Pygmy peoples is a threat to their legitimacy, but would prevent enslavement of Pygmies as they would enjoy their human rights. Others say that, as Congolese citizens, Pygmies are already protected by the laws of the country. This is contradictory as specific laws already exist to protect women, children, the disabled, and albinos.

Lastly, there is no national law on human or land rights defenders. Only the provinces of North Kivu and South Kivu have edicts (provincial laws) on human rights defenders generally, but they remain poorly enforced.

CONCLUSION

The territories of indigenous Pygmy peoples are increasingly sought after due to the riches they offer. Indigenous Pygmy peoples are exposed to serious dangers from state and private sector actors. Pygmy leaders are opposed to the grabbing of their land and natural resources. Despite the lack of a specific law, two provincial laws (edicts) have been adopted in the provinces of Sankuru and Mai-Ndombe.

Consequently, lands occupied by indigenous Pygmy peoples are not protected by legal titles or customary law certificates. Furthermore, collective ownership rights are not recognized in the current land law, unlike in Article 34 of the Constitution. Autonomous land management is a problem. Cases of despoliation, expropriation, and forced delocalization are the source of land conflicts and the expulsion of indigenous Pygmy peoples from their land, without consultation or their free, prior and informed consent.

267 cases of land conflicts have been documented to date, including conflicts between Pygmies and the Bantu in the province of Tanganyika, and conflicts in Idjwi in South Kivu. And yet, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, which the DRC voted for when it was adopted by the General Assembly, reiterates international legal standards guaranteeing indigenous peoples’ land tenure, confirming these peoples’ rights to preserve and strengthen their spiritual ties to their lands and resources and outlining the close ties between peoples and their lands, culture, identity, and integrity.

During the third cycle of the Universal Periodic Review of the Democratic Republic of Congo, May 7th, 2019, the Congolese government received 267 recommendations, of which 239 were accepted, including 8 relating specifically to indigenous Pygmy peoples. The implementation of these recommendations offers an opportunity to recognize and respect the rights of indigenous peoples.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Strengthen advocacy efforts on the adoption of a specific law regarding indigenous Pygmy peoples in the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

- Implement a national legal framework for the protection of land rights defenders in the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

- Release all legitimate defenders of Pygmy land rights incarcerated in the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

- Train land rights defenders on the safety and protection of human rights defenders; and

- Strengthen protective measures for defenders of the land rights of indigenous Pygmy peoples in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.